ADVENTURE

FROM SAINT-SAËNS TO COPLAND

PROGRAM NOTES

March 6, 2026

Danse Bacchanale

Camille Saint-Saëns

About the music

We encounter Danse Bacchanale in Act III of Samson et Delila, the only Saint-Saëns opera to survive. This work represents French lyricism at its best, the effectiveness of the score coming not only from the beautiful French melodies but also from the composer’s use of Hebrew and “Oriental” rhythms and harmonies. This is illustrated abundantly in the Bacchanale. It is notable that the familiar Biblical story, rendered in three Acts, was also adapted for oratorio in advance of its London premiere, as English law prohibited the depiction of Biblical scenes in dramatic performance. Ever since, it has been presented from the stage with great success both as opera and oratorio. In Act III, Samson - now blind, shorn of his hair, and chained - cries out to God for mercy, but he is soon led out to his final fate. The scene then shifts to the Temple of Dagon, where Samson’s ruin is celebrated by the Philistines with pomp and festivity, as illustrated by the darkly energetic “Bacchanale.”

About the composer

What a heady time to have lived! The subject of a biographical study by Marcel Proust…admired by Berlioz and Wagner…praised by Liszt as the finest organist in the world. And his pupils included Gabriel Fauré. This was Camille Saint-Saëns.

Born 1835 in the 6th arrondissement of Paris, Saint-Saëns considered himself a lifelong Parisien. Misfortune struck early, however, with the loss of his father to consumption (tuberculosis) when he was only a few weeks old. Though he demonstrated perfect pitch by the age of 3 and played for small groups beginning at 5, his mother sought to delay her prodigy’s coming to public attention. This occurred at a recital when he was 10 at the Salle Pleyel, where he performed the Mozart Piano Concerto in B flat and Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No.3.

He would go on to study at the famed Paris Conservatory and then to a succession of posts, first as organist in a large parish and then as professor of music at the Niedermeyer School. In 1871 after the Franco-Prussian War, he helped found the National Society of Music and in the same year, and produced his first symphonic poem, Le Rouet d'Omphale (Omphale's Spinning Wheel) , which, with Danse macabre, is the most frequently performed of his four such works. His opera Samson et Dalila, rejected in Paris because of the prejudice against portraying biblical characters on the stage, was given in German at Weimar in 1877, on the recommendation of Liszt. It was finally staged in Paris in 1890 at the Théâtre Eden and later became his most popular opera. This evening’s piece is an excerpt of that work.

Saint-Saëns was a traditionalist. Balance, beauty, structure and clarity were his watchwords. He had little interest in experimentation or emotion, nor was he enamored with the innovations of Debussy or Poulenc. According to Stravinsky, after attending a concert version of The Rite of Spring, the scandalized Saint-Saëns expressed the firm view that Stravinsky was insane. Though very much at odds with French enthusiasm for novelty at the turn of the last century, Saint-Saëns’ body of work earned him an enduring place in the pantheon of composers. His major works included more than a dozen chamber pieces, 5 piano concertos, 3 symphonies, 3 violin concertos, 2 cello concertos, and the symphonic (or tone) poems in addition to his choral works and 7 operas.

Symphonic Metamorphosis on Themes by Carl Maria von Weber

Paul Hindemith

About the music

In this work, Hindemith lifts four themes from some less familiar compositions by Weber, a composer of the late classical period who was best known for his operas and a smaller number of orchestral pieces. In the first, third and final movements, the material comes from All’Ongarese, Op. 60, for piano four hands, while the second movement quotes a theme from Weber’s overture to Turandot. The four movements are an allegro, a moderato, an andantino and a march.

As was the case with many 20th century composers, Hindemith went through several stages in his musical development. In his early years he embraced German Romanticism before leaning toward Expressionism, and later yet a form of counterpoint which at once looked back to Bach and forward to experimental approaches that untethered melody from the constraints of strict tonality.

About the composer

The rise of the Nazi Party impelled Hindemith to find a new homeland, leaving his native Germany in 1935 at the age of 40. As was the case with other great men in his place and time, he found the need to escape the swastika to find personal and artistic freedom. Hindemith was married to a woman of Jewish ancestry, had made recordings with Jewish musicians and refused to repudiate his relationships. Moreover, his form of artistic experimentation put him afoul of Goebels and other party leaders who described his music as “degenerate.” Across time and location, it seems, Fascism has sought to limit human expression and bend it to the will of the government, the Party, and those who seek power for power’s sake.

Born in Hanau, Germany 1895, Hindemith pursued music from an early age despite the opposition of his father. He ran away at the age of eleven, studying violin and viola on his own and playing in cafe and theatre orchestras. Later, he attended the Frankfort Conservatory where he won early recognition for his first String Quartet, Op. 2. After a stint in the German army, he joined the orchestra of the Frankfort Opera, where he served as concert-master for an eight year period.

His early attempts at opera composition were less than entirely successful. From 1922, however, his output, including a second String Quartet and other chamber works, a song cycle and a full-length opera, Cardillac, propelled him to prominence. Over this time, Hindemith’s style became increasingly objective, incorporating polyphonic procedures in an atonal idiom. His interest in this form of contrapuntal writing proceeded without particular regard for popular tastes or preferences. It was the appearance of his Mathis der Maler (1934) that put the composer at odds with Nazi leaders. When his ally, the conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler, published a fiery letter of protest against the Party’s attempts at censorship, the wrath of Hitler himself descended on both men. Hindemith left the country, first for Turkey, and then for America, which he would make his longtime second home. There he continued his work, serving in a variety of roles including a professorship at Yale University. Among the compositions of this period was the Symphonic Metamorphosis that we hear this evening.

He would return much later to Germany (1949) for a brief visit to much acclaim. In 1953 he went to live in Zurich but made frequent return visits to the US over the ensuing decades. He died in Berlin during a tour conducting his last composition, November 12, 1963.

Norfolk Rhapsody No. 1 in E minor

Ralph Vaughan Williams

About the music

Drafted between 1905 and 1906, the three orchestral rhapsodies of Vaughan Williams were adapted from a series of folk songs that the composer discovered in the county of Norfolk England, and more specifically in the fishing port of King’s Lynn. Only the first Rhapsody has survived in its entirety. The composer’s original intent was for the three works to create a kind of folk song symphony, beginning with Rhapsody No. 1 as the first movement. The work introduces two songs, The Captain’s Apprentice” and “The Bold Young Sailor,” continuing to a main allegro section featuring adaptations of “A basket of Eggs,” “On Board a Ninety Eight” and “Ward, the Pirate,” tunes that he found in the north end of King’s Lynn, home to much of the local fishing community.

About the composer

Vaughan Williams came late to the study of music, and his parents were initially uncertain of his prospects for success. Born 1872 in Gloucestershire, England to a well to do family with liberal values, he enrolled at 18 in the Royal College of Music and later at Cambridge, studying history and music. There he had the opportunity to create lasting friendships with a number of notable intellectuals, including the philosophers G.E. Moore and Bertrand Russell. During a second spell at the RCM, he developed a close working relationship with fellow student Gustav Holst. The two would critique one another’s compositions while writing, each having an important influence on the other’s work.

Vaughan Williams did not come into his own as a composer until his late 30s, however, under the influence of his mentor Maurice Ravel, who helped him to find his own artistic voice. He had a particular interest in making music accessible to all, eschewing the style of Brahms and Wagner. During a compositional career that would last until 1958, the year of his death, he would write more than 80 songs, a number of choral works and a variety of works for the stage. He is best known, however, as one of the 20th century’s most important symphonists, writing 9 in all in addition to several other orchestral works such as the Norfolk Rhapsody No 1. that we hear in this concert.

Rodeo Suite

Aaron Copland

About the music

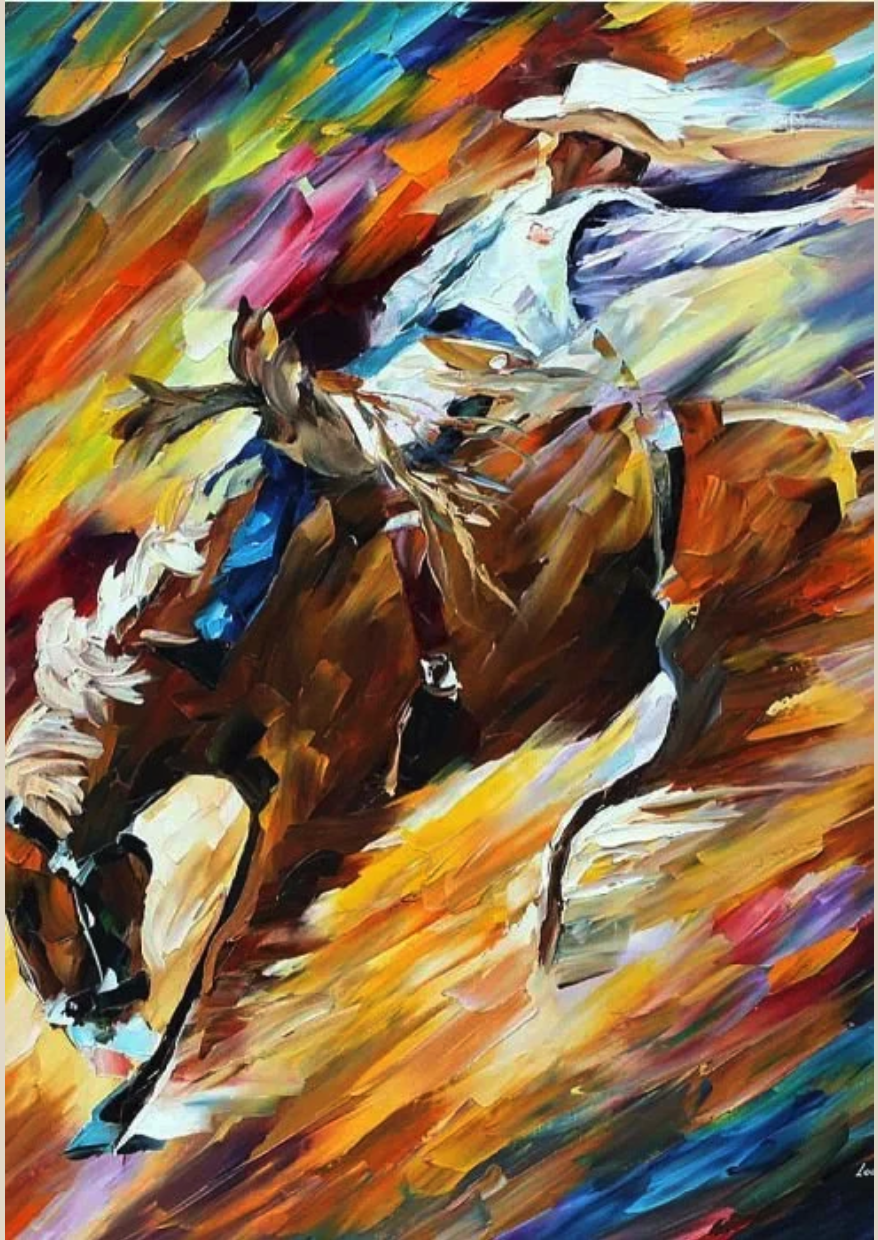

The four-movement suite is based on Copland’s ballet score Rodeo, written in 1942. The scenario and the choreography were the work of Agnes de Mille. We find ourselves returning to the American West, the same place and time that Copland explored in his previous, successful ballet “Billy the Kid.” The ballet’s plot involves the adventures of a cowgirl at a rodeo who has attracted the romantic attentions of a wrangler and a roper. The roper wins out. Copland adapted the full score of his ballet in this orchestral suite, applying the following titles: Buckaroo Holiday, Corral Nocturne, Saturday Night Waltz, and Hoedown. The last of these has become a particular favorite not only in its original orchestral version, but also in an arrangement for violin and piano.

About the composer

It would have seemed unlikely that Aaron Copland, born 1900 and raised in Brooklyn by a distinctly unmusical family, would become the “dean of American music” and the most successful composer of his generation. Historians say that a concert by Paderewski that he attended as a teenager sparked his interest. While attending Boys’ High School in Brooklyn, he began taking piano lessons and then studied with a Rubin Goldmark who taught him the fundamentals of harmony. Copland was far more interested than his teacher in the “moderns,” however, and began experimenting in modes far beyond his teacher’s compass. In college, he took up musical study in France with the help of his family, finding mentorship with Nadia Boulanger. Returning to America at 24, his rise was meteoric. By the 1930s, however, he took stock of his compositional work, realizing that with the exception of a few pieces written in a jazz idiom, most of his output was cerebral and esoteric. He yearned to write music for everyday people.

Copland began to address new audiences through simplicity, and as important, through the use of familiar folk material. His first such effort was El Salon México, introduced in 1937. It was a tremendous success. Other works followed - the ballets Billy The Kid, Rodeo (1942), and then Appalachian Spring, written for Martha Graham, debuting October 30, 1944 in Washington. Other works influenced by American folk music included his opera The Tender Land, and works for the screen, such as Our Town, The Red Pony and Of Mice and Men.

During the 90 years of Copland’s life, he would champion American music, serving as mentor to many, including Lucas Foss, Leonard Slatkin, Julia Perry, Ned Rorem and perhaps most notably, Leonard Bernstein. He was the founder of the summer Yaddo Festival and of the Copland-Sessions concert series, and played an important role over many years at Tanglewood as a teacher to many aspiring musicians and composers. Copland died in Sleepy Hollow, New York in 1990.